– Vinod Pavarala

Resistance to media globalization is often predicated on the well-founded assumption that the state and transnational commercial actors would control and direct the development of technology to suit their own interests. Since the mid-1990s, we have had to face the irony of proliferation of media outlets, on the one hand, and the rapid decline in the range and quality of information available, on the other.

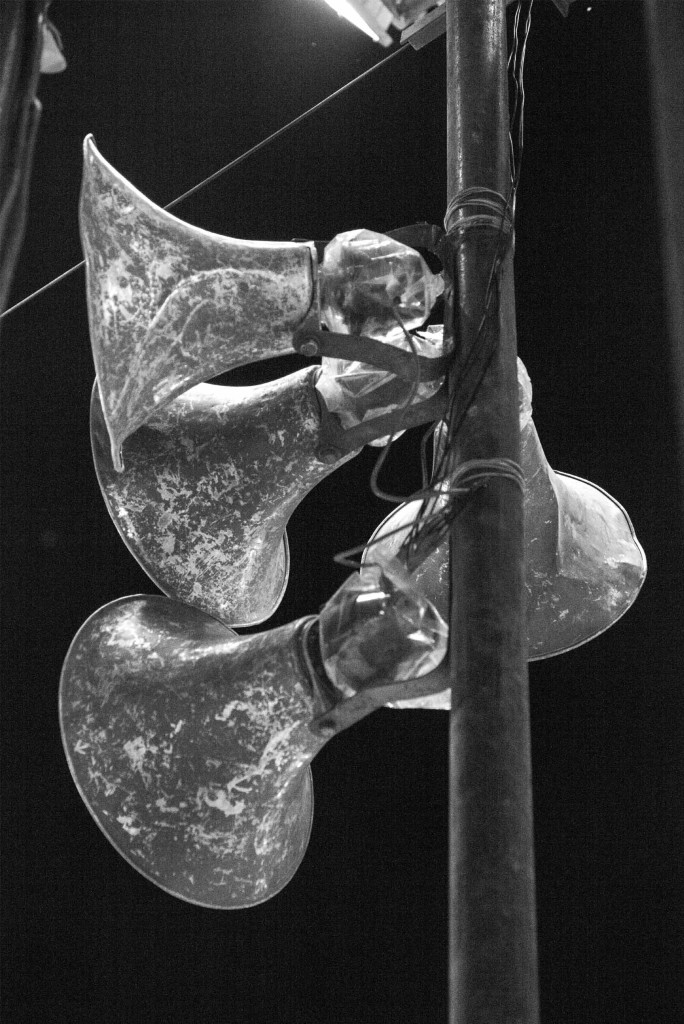

A number of civil society organisations in India have challenged the hegemonic roles played by state-centred or market-run media, and have been propagating the need for popular, community-based, alternative media such as people’s theatre, small local newspapers, community radio, participatory video, and alternative documentaries. The emergence of these media, it was suggested, would help revive the spirit of development communication envisaged by some of the communication pioneers in the country. The community radio initiatives by several groups across India for a share of the airwaves, which are ‘public property’, are one significant indication of this popular resistance.

In order to re-energize civil society weakened by state and corporate-dominated media, citizen groups, community organisations, and media activists across the world have been advocating for an appropriate institutional space. By taking stock of the political realities associated with broadcasting in India, community radio activists in India made a case, more than a decade ago, for the functioning of radio in the country to be based on the principles of “universal access, diversity, equitable resource allocation, democratisation of airwaves, and empowerment of marginalised sections of society” (DDS, 2000).

Development Communication: the dominant paradigm and beyond

There is a long, chequered history of the so-called ‘dominant paradigm’ in development communication, which emerged in the post-World War II years as newly independent Asian, African, and Latin American countries ventured out to become progressive, self-sustaining and industrialized. The use of the term ‘development’ became associated with themes like modernization, economic growth and technological diffusion leading to centralized planning, large-scale industrialization, and the expansion of basic communication infrastructure with a top down approach. The role of mass media was to motivate change in attitudes, beliefs, and behaviours.

The post-colonial political and policy elites in India enthusiastically embraced this vision of using communication and media as tools of persuasion, directed especially at the rural poor, to change their attitudes and bring about desirable social change. Communication campaigns promoting family planning and green revolution agriculture are now the stuff of legends in India’s development story. The Radio Farm Forums organized in Maharashtra in the mid-1950s to impart information on improved agricultural practices and the massive Satellite Instructional Television Experiment (SITE) in the mid-1970s in six States are both significant examples of this approach.

The mid-1970s saw disenchantment with the postulates underlying the modernization and economic growth as they did not correspond to the social realities and cultural milieu in the developing countries. Evaluation reports of extension programs indicated that there was little evidence of the ‘trickle down’ effect because the rural social structures thwarted all attempts to reach the poor. The extensive mass media networks degenerated into being tools of government propaganda or a source of superfluous entertainment for the urban middle-class. The few attempts to use mass media for development were rendered ineffective by the elitist bureaucracies and the existing social hierarchies. In India, the delegitimisation of the state during the Emergency, disenchantment with party politics, and the emergence of social movements and non-governmental organizations since the 1980s around issues such as ecology, gender equity, and rights of indigenous people and peasants have contributed to a comprehensive critique of the dominant paradigm and the formulation of an alternative, participatory development discourse.

These new approaches to communication emphasised the need to establish decentralised media systems with a more ‘receiver-centric’ rather than ‘communicator’ orientation, and with accent on exchange of information and ‘meanings’ rather than on persuasion. Community-based independent media, such as community radio, participatory video and popular theatre are now perceived by media activists and grassroots organizations as a means of enabling rural people to manage their own development and to acquire a sense of control over its course through self-management.

Broadcasting Policy in India

The history of the broadcasting system in India reveals that one of the main factors that perpetuates status quo is the desire of the state to retain control. In fact, the attitude of successive governments even after nearly seven decades of Independence have unmistakable traces of the norms set by the British who introduced organised broadcasting in the country. In 1933 the Indian Wireless Telegraphy Act was brought into force, which made the possession of radio receivers and wireless equipment without a license an offence. The Indian Government’s current monopoly over radio and television broadcasting derives from this Act together with the Indian Telegraph Act, 1885 which gives exclusive privileges of the establishment, maintenance and working of wireless apparatus to the Central Government.

After the termination of the Emergency, during which credibility of the state-run media took a severe beating, the country’s first non-Congress government pledged ‘genuine autonomy’ to the electronic media which had hitherto been reduced to a vehicle for political propaganda. For about two decades, successive governments in New Delhi sent ‘mixed signals’ about autonomy with a series of proposals which eventually culminated in the notification of the Prasar Bharati Act by Parliament in 1997 (Kumar, 2003).

As cable-delivered foreign satellite television channels started making rapid inroads into the country in the 1990s, the argument for autonomy was expressed in terms of competitiveness and commercial viability. Conditions for broadcasting changed radically in the early 1990s with the so-called ‘satellite invasion’ (Pavarala and Kumar, 2001). In February 1995, the Supreme Court delivered a historic judgment in Ministry of Information and Broadcasting v. Cricket Association of Bengal. The Court ruled that: ‘Airwaves constitute public property and must be utilized for advancing public good’. A number of civil society organisations and media activists took the 1995 Supreme Court judgment as a point of departure and started making efforts to carve out an alternative media sector in India, which would neither be state-run nor market-driven. These groups saw radio as a tool for empowerment, an appropriate technology to conscientise and build capacities of communities to become active participants in grassroots development.

Community Radio in India: Redefining the Public Sphere

Even as radio was commercialized through private FM stations, the long-standing demands for a third tier of independent, not-for-profit broadcasting in the country yielded only a restricted ‘campus’ avatar of community radio in the first quarter of 2003. That allowed “well-established” educational institutions to set up FM transmitters and run radio stations on their campuses. This decision diluted somewhat the hegemony of the state and market over radio, but the government for a long time resisted the demands for opening up this sector, under misplaced apprehensions that secessionists, militants or subversive elements would misuse the medium. Several non-governmental organisations and media-activist groups campaigned for nearly a decade, culminating in a more inclusive community radio policy approved by the Union Cabinet in November 2006. The new expanded policy permitted NGOs and community-based groups, with a track record of developmental work, to set up Community Radio Stations (CRS). In the 10 years since a putative community radio policy was announced by the Government of India we now have about 180 operational stations licensed under the policy, of which about a third are those run by NGOs.

Ten Years After: A Blurred Development Vision?

Civil society organizations, media activists and advocates who campaigned for opening up of airwaves had emphasized the potential of using community radio for development, rather than foregrounding what seemed to be the more radical framework of communication rights. Many of these groups and individuals had themselves emerged in the crucible of the post-Emergency civil society ferment and had strong belief in the power of non-governmental action in articulating an alternative development vision from that of the state.

Research conducted by our team at the UNESCO Chair on Community Media over the last decade (Pavarala and Malik, 2007; Pavarala, Malik, and Belavadi, 2010) compels us to reflect critically on the role of civil society organizations in the development of community radio in India. The funding imperative, the policy specifying NGOs as the eligible applicants, and the overall developmental framework led to the growth of community radio in India largely through the efforts of NGOs. While some of the best examples of genuine grassroots community radio in India come from NGO initiatives, some organizations are beginning to enter the arena solely to further the organizational objectives and they take to non-participatory methods under pressure from donors to ‘scale-up’ operations and to demonstrate ‘impact’ on behavior change. The implications of this incipient NGO-ization of community radio in India are beginning to be felt across the sector.

A community radio project in eastern India translated its ‘rights based’ approach into government officials holding forth on various schemes to which the rural poor are entitled. Without any community voices pointing to loopholes in the implementation and bereft of any lively discussions on the scheme, the expert-driven broadcasts were reduced to mere extensions of state radio. A second change that happened at this NGO-run station is that an economy of scale was sought to be achieved, apparently at the behest of certain donors, by expanding coverage area. It not only led to the decline in participation of the people in the villages in the selection of issues, planning and production, and post-production activities, but also to the dropping out of all women reporters who found it difficult to negotiate such a large geographical area without adequate security or transport. With the gradual shifting of the programme towards an information dissemination paradigm directed and driven by fewer and fewer people, it did not help strengthen individual and community communication capacities and decision-making abilities.

In another comprehensive study done more recently by the same team of three community radio stations in the Bundelkhand region (Pavarala, et al, 2013), it was found that the mandates of two of the stations funded by a multilateral agency significantly showcased the social and developmental agendas of the funding agency as well as those of the NGOs. The overarching approach was to ‘cater’ to the perceived ‘information needs’ of the community, bordering on being instructive and prescriptive. The stations that were being funded by the multilateral agency got accustomed to a steady flow of funds, making them put in place unsustainable practices such as hiring a large number of salaried staff members. As the agency announced its withdrawal from the project, the stations suddenly realized the challenges of such a donor-driven model of community radio.

While the way some of the NGOs are deploying radio is unwittingly aligning them with an older state-centred paradigm of broadcasting for development, there have been other developments in the community radio sector that are threatening its autonomy from the state more directly. The Ministry of I&B recently launched a Community Radio Support Scheme mainly to subsidize the acquisition of technology by stations. While public funding of community radio is welcome, it should have been set up as an autonomous fund as in many other countries instead of a government Ministry controlling the purse strings tightly. In other words, the present government sees community radio as an ideal low-cost, last-mile delivery platform for the many government schemes such as Swachch Bharat, Beti Bachao, and Jan Dhan Yojana,. If community radio were to function merely as All India Radio, doling out information that would rally people around ‘national’ development goals and mould them into ‘good’ citizens through top-down, expert-driven communication, the years of struggle for an independent space would have been in vain. The troubling aspect of state funding is whether it is preferential advertising or funding for content production by interested ministries, these have the effect of reducing community radio to a supplicant in a complex patron-client relationship. Combined with the increasing NGO-ization of community radio in India, negotiating an acceptable relationship with the state has become a key challenge for the sector as a whole.

Conclusion

The trends discussed above must make us reflect on the strategic choice of the development paradigm within which activists and advocates in civil society have pushed the CR agenda in India. If community radio were to contribute to the making of a subaltern public sphere, the time has come for the movement to shift to a more radical, communication rights paradigm.

It was hoped that community radio would offer to people opportunities to debate issues and events of common concern and to set counter-hegemonic agendas. The forging of ‘subaltern counterpublics’ would, it was envisioned, help expand the discursive space, eventually facilitating collective action and offering a realistic emancipatory potential.

A decade after the community radio policy was announced, there are many aberrations that have emerged on the Indian community radio landscape. On current evidence, it seems like the entire sector, marked by a complex play of collaborations between the state, the NGOs, multilateral agencies, and other related stakeholders, is handicapped by a blurred vision that seems to reproduce older paradigms of development communication.

Vinod Pavarala teaches communication at University of Hyderabad.

vpavarala@gmail.com

References

Agarwal, Binod C. (2006). “Communication Technology and Rural Development in India: Promises and Performances,” Indian Media Journal, Vol.1, No.1, July-December, pp.1-9.

Deccan Development Society (DDS). 2000. The Pastapur Initiative on Community Radio Broadcasting.

Kumar, Kanchan. 2003. “Mixed Signals: Radio Broadcasting Policy in India,” Economic and Political Weekly, May 31.

Ministry of Information and Broadcasting (MIB). 1996. Broadcasting Bill: Issues & Perspectives. New Delhi.

———. 2000. Prasar Bharati Review Committee Report. New Delhi: http://mib.nic.in/nicpart/pbcont.html

Ninan, Sevanti. 1998. ‘History of Indian Broadcasting Reform’, in Monroe E. Price and Stefaan G. Verhulst (eds.), Broadcasting Reform in India. Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Pavarala, Vinod and Kanchan Kumar. 2001. ‘Broadcasting in India: New Roles and Regulations’, Vidura, July–September, 3.

———. 2002. ‘Civil Society Responses to Media Globalization: A Study of Community Radio Initiatives in India’, Social Action, January–March, 52(1): 74–88.

Pavarala, Vinod, Kanchan K. Malik, and Janardhan Rao Cheeli (2006), “Community Media and Women: Transforming Silence into Speech,” in A. Gurumurthy, P. J. Singh, A. Mundkur and M. Swamy (eds), Gender in the Information Society: Emerging Issues, New Delhi: Asia-Pacific Development Information Programme, UNDP and Elsevier, pp. 96-109.

Pavarala, Vinod and Kanchan K. Malik. 2007. Other Voices: the struggle for community radio in India, Delhi: Sage.

__________. 2008. Communication for Social Change: Evaluating Chala Ho Gaon Mein in Jharkhand. Research Monograph. UNESCO Chair on Community Media, University of Hyderabad.

Pavarala, Vinod, Kanchan K. Malik, and Vasuki Belavadi. 2010. On Air: A Comparative Study of Four Community Radio Stations in India, Research Monograph, UNESCO Chair on Community Media, University of Hyderabad.

Pavarala, Vinod, Kanchan K. Malik, Vasuki Belavadi, and Preeti Raghunath. 2013. On Air: A Study of Three Community Radio Stations in the Bundelkhand Region of MP and UP, Research Monograph, UNESCO Chair on Community Media, University of Hyderabad.

Pavarala, Vinod. 2015. “CR in India: Whose vision? Whose voice?” CR News, 6:2, April-June.![]()