– Kush Badhwar

In what state does media come to us and once it enters our lives, how does it affect our existence? What life does media live after it has been produced, performed or published? What is the role of the past in our lives today and how does it make itself apparent? Throughout its existence, the Anveshi Broadsheet has often republished, re-enacting the past to consider its effect on the present. In this issue we see the reappearance of Kanshi Ram’s introductory editorial from The Oppressed Indian (1979), excerpts from Edward Said’s Covering Islam (1981) and B. N. Uniyal’s “In search of a Dalit Journalist”(1996). This section of the broadsheet turns attention to such attempts to recover, remember or record a past, through various glimpses at the ongoing life of media: Shubhangi Singh looks at the use of media in the process of creating a state identity in Telugu University’s School of Folk and Tribal Lore; I speak with two Hyderabad-based film-makers about how existing media has figured in the conception or making of their films; and finally, or rather firstly, in the following paragraphs, we meander in and around the archive, a hazy site that features in our thinking as a place where the traces of our past, including the great amounts of media materials we are presently generating, may end up.

In what state does media come to us and once it enters our lives, how does it affect our existence? What life does media live after it has been produced, performed or published? What is the role of the past in our lives today and how does it make itself apparent? Throughout its existence, the Anveshi Broadsheet has often republished, re-enacting the past to consider its effect on the present. In this issue we see the reappearance of Kanshi Ram’s introductory editorial from The Oppressed Indian (1979), excerpts from Edward Said’s Covering Islam (1981) and B. N. Uniyal’s “In search of a Dalit Journalist”(1996). This section of the broadsheet turns attention to such attempts to recover, remember or record a past, through various glimpses at the ongoing life of media: Shubhangi Singh looks at the use of media in the process of creating a state identity in Telugu University’s School of Folk and Tribal Lore; I speak with two Hyderabad-based film-makers about how existing media has figured in the conception or making of their films; and finally, or rather firstly, in the following paragraphs, we meander in and around the archive, a hazy site that features in our thinking as a place where the traces of our past, including the great amounts of media materials we are presently generating, may end up.

For some the past is a non-issue, something that does not figure in their day to day dealings. For others it is painful and needs to be forgotten. For some the past has been ignored and others need to be made to realise it. For others still, it is glorious. For some it needs to be rescued from being destroyed at a catastrophic pace. For others it is something to go back to when there’s nothing better to do. Some would like to learn from it in order not to repeat mistakes. It takes power to collect it. In turn, collecting it generates power.

Eye-level with the cityscape the metro swishes above the uncrossable road. The line it travels on is one kind of a pipe among many that constitute the city. These pipes lead seemingly everywhere, except to places they haven’t reached yet — the borders of urban imagination. Apart from metros, these pipes transfer various things including water, electricity, online presence and the songs streaming to passenger headphones. The simultaneous flow of all the pipes is luxury, but as long as any one pipe is flowing there’s enough to keep one distracted. Despite having been promised uninterrupted flows at high speeds, the stream to one passenger’s headphones sputters to an end. Swiping right, the passenger enters their ‘archived chats’, a section that doesn’t need the real-time flow of a pipe to be read. Loading earlier and earlier, the passenger recounts a conversation backwards, getting lost down memory lane in a swirl of text, sound, images and emojis. Where are we? Out of the window, the sun pokes out his tongue and winks. Certain things jump out and other things recede out of view. One of these is a state archive, a dated piece of architecture coated in peach. What’s in there?

seemingly everywhere, except to places they haven’t reached yet — the borders of urban imagination. Apart from metros, these pipes transfer various things including water, electricity, online presence and the songs streaming to passenger headphones. The simultaneous flow of all the pipes is luxury, but as long as any one pipe is flowing there’s enough to keep one distracted. Despite having been promised uninterrupted flows at high speeds, the stream to one passenger’s headphones sputters to an end. Swiping right, the passenger enters their ‘archived chats’, a section that doesn’t need the real-time flow of a pipe to be read. Loading earlier and earlier, the passenger recounts a conversation backwards, getting lost down memory lane in a swirl of text, sound, images and emojis. Where are we? Out of the window, the sun pokes out his tongue and winks. Certain things jump out and other things recede out of view. One of these is a state archive, a dated piece of architecture coated in peach. What’s in there?

To define the archive, let us turn to a book bound hard in regal maroon. I can’t tell you its author or title or publisher, because those pages are missing. In fact, it’s a book salvaged from a kabadiwala just a few days ago. The introduction works through a series of situations in which a document could end up in an archive, finally arriving at this definition: “A document which may be said to belong to the class of Archives is one which was drawn up or used in the course of an administrative or executive transaction (whether public or private) of which itself formed a part; and subsequently preserved in their own custody for their own information by the person or persons responsible for that transaction and their legitimate successors.” At the bottom of the page that carries this definition is a purple stamp: “STATE ARCHIVES LIBRARY ANDHRA PRADESH HYD,” indicating where this book once belonged. But why is it no longer in “the class of Archives”? Does the definition still hold (now that the book carrying the definition is no longer preserved by the archive, but has gone to a kabadiwala instead)?

Perhaps entering the state archive will shed light on this.

Unlike a museum, there’s no ticket-window. Should we be in here? To access the contents, our best foot forward would be a letter with an institutional letterhead that carries an indication of our intention and someone’s signature at the bottom. It is unlikely the authenticity of this letter will be verified as long as we play by the rules of the archive. We gain entry. There exist both written and unspoken ways to behave in this place. An identification number/letter combination will be issued and we will now have general access to the archive. Our navigation around the building’s accessible and inaccessible parts will now depend on the relationships forged with the archive’s staff or their superiors. For all intents and purposes, the staff will now perceive and identify us as a ‘research scholar’. This is because, apart from staff, it is normally ‘bona fide’ research scholars that inhabit the site. We only sense the unending array of documents and files stored within.

How much will our sudden rise in rank allow us to retain our publicness?

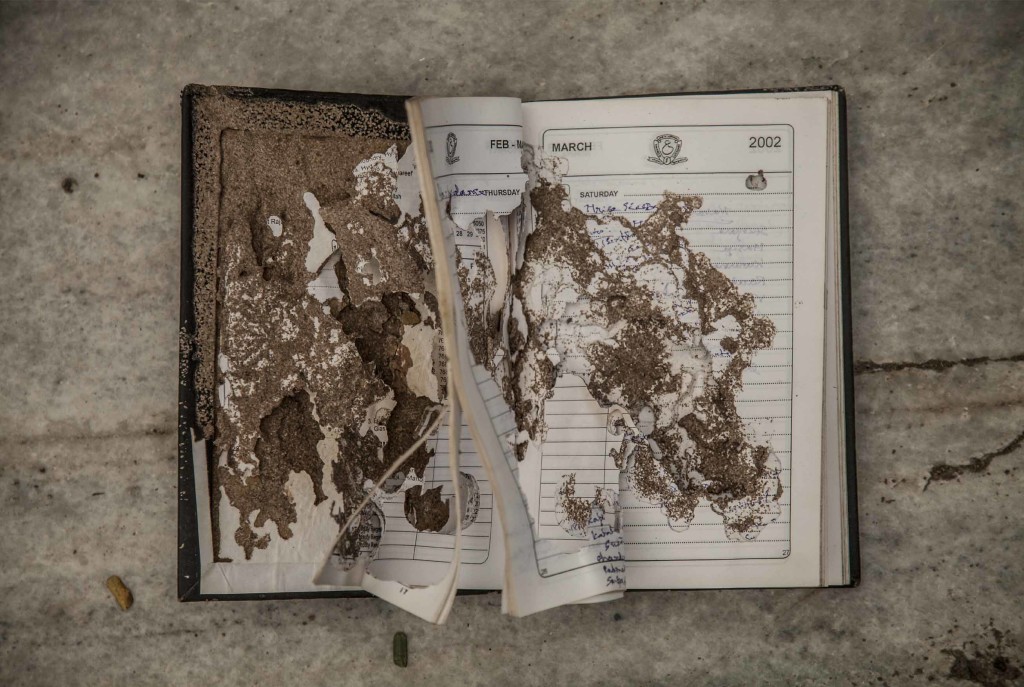

An ordinary member of the public possessing no other specific designation rarely enters the archive. There could be a variety of reasons for this: members of the public may be too busy outside the archive compound and archival contents may be too dry to enter their lives; the archive may lack resources to engage with members of the public; and there may exist an inherent fear towards the safety of archive contents in the hands of the multitude. The archive has also identified the ‘enemies of records’ it keeps within its own walls. The enemies of records differ from the bickering content between records. These enemies pose a threat to all records no matter what side they take. They range from bad handling to rats to things we cannot see that exist on a molecular level. A few methods have been devised to protect archival contents from these threats, all of which require varying amounts of infrastructure to implement and maintain. According to the methods our archive uses, one can get a sense of how well resourced our archive is and if we compare its methods to those used by other archives both around the country and the world, this sense can translate to an order of archives in terms of privilege and importance. While this order may not strictly reflect on the contents of our archive, if the content is deemed more important than the local archive’s ability to look after it, another archive, higher up the order, may extend its excess resources to our archive.

The archive contains history, but what is the history of the container? It may have emerged from a split in another archive. More such containers may emerge from it in the future as a result of the same, or at least similar, processes. At the sign of a split, engaged members of the public will raise concern. What material will end up in what ‘state’? A split might suddenly acknowledge certain records that have circulated or lay dormant amongst the public for sixty years or more. In this period of time, similar records might be lost, forgotten, destroyed or damaged beyond repair. The pieces that remain do so in the possession of individuals who may be authors, publishers or those who are interested in the work. What happens if they are found? Owners of these records will feel proud of their foresight, that what they said so long ago or possessions they kept for so long are now worthy to enter the archive. By now, these people might be in power. Their former expression of personal or public sentiment and remnants of ritual will now perform new roles as records on the shelves of the archive. But let us not linger on this long-brewing moment of acknowledgement. Let us now exit the gates of the archive and view the matter from the outside.

What will we do now that we are out?

Kush Badhwar is India Foundation for the Arts’ Archival Fellow across 2014-2015.![]()