Based on the Book “Why Loiter”1

– Madhurima Majumder

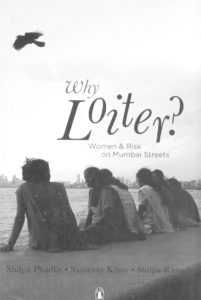

Shilpa Phadke, Sameera Khan and Shilpa Ranade in their book Why Loiter: Women and Risk on Mumbai Streets place loitering and risk-taking as an important feminist concern in women’s access to public space. This book points out that women are only granted conditional access to the public space as long as they “demonstrate respectability and purpose”. Women don’t belong to public spaces and hence their access can be threatened any time. Women across class, caste, religion, none are exception to this rule. This article is a brief overview of this book and the movements around women in public space that followed.

Mumbai Streets place loitering and risk-taking as an important feminist concern in women’s access to public space. This book points out that women are only granted conditional access to the public space as long as they “demonstrate respectability and purpose”. Women don’t belong to public spaces and hence their access can be threatened any time. Women across class, caste, religion, none are exception to this rule. This article is a brief overview of this book and the movements around women in public space that followed.

Who do our cities belong to?

The agreed upon norm is that the rightful claim over the public spaces of our cities belong to men, whereas women are only allowed to use it temporarily to get about their lives. In fact, the right to have a public life as well as access to public space was not something that most women enjoyed even a century back. City and definition of citizenship, this book points out, were established by demarcating the “unbelongers” like women, migrants, landless, slaves, etc. Women were not seen as autonomous citizens and had to be under the guardianship of a man. In modern politically democratic states, women are granted equal citizenship. However, this remains true in theory.

One might argue that times are changing and more and more women are stepping in the public space, especially post liberalization. In fact we are doing a project on women who are staying on their own, outside the scope of the familial guardians, on their own. However, with women coming to cities for education and employment, these spaces often function as proxy guardians. Thus, women still do not enjoy equal access. Transgression from the path of respectability or purpose can threaten their access to public space.And hence after every case of sexual violence, the first point of interest seems to be “what was she wearing”, “what was she doing there?” Women are still not autonomous individuals. Women and their lives remain as needing to be closely guarded.

The modern state and the economy have created a historical situation where women are allowed limited access to public space, but in turn they have to follow and sometimes even become moderators of patriarchal code.

Code of conduct for Women

In fact, the supervisory gaze is so pervasive that women often internalize the values and self-censor. Women are discouraged from going out due to concerns for their own safety. Yet when there is choice between respectability and safety from violence, women are often forced to choose the former. This points to the fact that the real concern is to guard the‘honour’ of the woman, immaterial of whether she has to face violence or not.

Ladies hostels have strict curfew timings in place for the “safety” of the women and yet often fail to have proper infrastructural measures that are more relevant in keeping them safe. There have been times when women have been turned away failing to reach hostel within curfew timing, which seems counterintuitive if the central concern was their safety! What this shows is that women have no right to take risks and those who do, are interpreted as “calling for trouble” and are disciplined.

In fact women do not have the permission to be comfortable with their presence in public space.There is a crippling burden of being on guard the moment they step out. Women feel the need to avert gazes, look purposeful and occupy as little space and look as inconspicuous as possible.”This is often both a strategy to avoid groping hands and a reflection of women’s conditional access to public space.” On the other hand the average man has a different level of entitlement to public space.

It would have so liberating if women didn’t have to treat every encounter with a stranger or a new place as a potential threat. Women cannot belong to the city, or its public space if they don’t feel comfortable and relaxed in public spaces. It would indeed be liberating for women to be at ease and actually enjoy the world outside. The book aptly points out how in public spaces women without any visible sign of purpose are unimaginable. A city were women are sitting or standing with nowhere to go, chatting whistling, laughing, breast-feeding, is a radically different city from the ones we live in. This desire to be able to own public space was so identifiable that this book Why loiter and the movement that followed from it resonated with women across not only in India, but women across South Asia. It is to this desire that the book (2011) directly speaks and places the right to loiter as not only legitimate but a central feminist demand around the issue of women’s access to public space.

Loitering as a political act

In the debate on women and their access to public space, this book succeeds in moving beyond the limiting scope of debates around securitization. It rightfully shifts the focus from “protection” to a “rights” based discourse. After the infamous Delhi Rape Case of 2012, much of the focus has been on discussions around security measures for women in public spaces. However, many women’s collective organized meetings and events that aimed at occupying public spaces that were outside the acceptable or norm for women. Hyderabad for Feminism organized a Midnight March March on January 5, 2013. The march was organized to relook at the assumptions regarding safe and unsafe hours for women as well as to send a message to men that women are to be respected as fellow humans, even in the night. A collective in Pakistan, called ‘Girls at Dhaba’ tried to occupy public spaces that were largely male dominated, such as roadside eateries.This collective of women were troubled by the disappearance of women from the public space and tried to reclaim a world where all genders have equal access. Many movements were in fact organized in several cities as a response to the publication of this book. The Meet to Sleep movement was started by Blank Noise, a feminist collective in Bangalore in 2015. Women took to their public parks and spent time loitering, sleeping or just simply hanging out. 500 women and girls, across 25 big and small cities like Bangalore, Mumbai, Dimapur, Kohima, Surat, Panjim, Jaipur, Vadodra, Jodhpur, Islamabad, Karachi, and Ranchi joined this movement. Another initiative started by this collective around the same time was #walkalone, which asked women to

be their own action heroes and take a walk alone in a part they never had before. The intention behind this movement was to collectively fight fear that women have long been taught to carry. These women through individual and collective action tried to create new experiences for themselves and those around them and through that build new narratives of belonging, connection, and pride in place of fear, shame and violation. I Will Go Out was a nationwide march carried on 21 January 2017 to demand women’s right to fair and equitable access to public spaces. Women and men marched across 30 cities and towns as a response to the mass molestation of women that happened in the streets of Bangalore on during New Years Eve celebrations.

Resilience in the face of fear

In present times, with the rise of neo traditionalism the presence of the unbelongers of the city – women, Dalit, Muslims, migrants, couples have become even more precarious. The present shift in politics and public opinion indicate that the code of respectability and purpose are getting enforced more strictly and any transgression is discouraged more violently.

Why Loiter and the several movements that sprang up in big and small cities indicate that there is a growing problem and we can’t wish it way. These movements, a cynic might argue do very little in terms of actually changing the larger structures. However, trying to understand and articulate our tenuous relation with public space might not alter the exclusionary structures that limit our relation with the public space, but it does change one thing. It doesn’t stay invisible.

Madhurima Majumder was part of Anveshi City and Sexuality project in 2016-19 and City and Sexuality project in 2016-19 and City and Sexuality project in 2016-19 and currently teaches at Rajiv Gandhi National Institute of Youth Development, Sri perumbudur, Tamil Nadu. madhurima.majumder89@gmail.com.

1Phadke Shilpa, Sameera Khan and Shilpa Ranade . 2011. “Why Loiter: Women & risk on Mumbai Streets”, Viking, Penguin.