– Madhumeeta Sinha

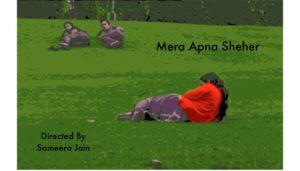

Several Indian cities, jockeying for investment and viability on a ‘global’ map, are desperately being modernized—but what does this process make of their inhabitants? There is constant talk of infrastructure: newer roads, hospitals, educational institutions, shopping malls, high-rise apartments, theatres, and theme parks are said to be pushing urban boundaries high and wide, and perhaps creating job opportunities for some of the aspirants pouring into the cities. The city’s inhabitants, old and new, are caught in their everyday struggles to survive and settle in the city. One presumably acquires the right to a city by living in it, observing its rules and codes, using its infrastructure, contributing to its growth, feeling at home in it. In this sense cities are supposed to be open to all inhabitants, but then reality bites! The relationship between the city and its inhabitants is based on, and negotiated through, older and newer modalities of power. I will focus here on the gender dimensions of urban existence in India—how the city propels certain relationships and behavior models, which in turn encode gendered norms of belonging to the city— through a reading of Sameera Jain’s compelling documentary film Mera Apna Sheher (2011).

modernized—but what does this process make of their inhabitants? There is constant talk of infrastructure: newer roads, hospitals, educational institutions, shopping malls, high-rise apartments, theatres, and theme parks are said to be pushing urban boundaries high and wide, and perhaps creating job opportunities for some of the aspirants pouring into the cities. The city’s inhabitants, old and new, are caught in their everyday struggles to survive and settle in the city. One presumably acquires the right to a city by living in it, observing its rules and codes, using its infrastructure, contributing to its growth, feeling at home in it. In this sense cities are supposed to be open to all inhabitants, but then reality bites! The relationship between the city and its inhabitants is based on, and negotiated through, older and newer modalities of power. I will focus here on the gender dimensions of urban existence in India—how the city propels certain relationships and behavior models, which in turn encode gendered norms of belonging to the city— through a reading of Sameera Jain’s compelling documentary film Mera Apna Sheher (2011).

Mera Apna Shehar is a revealing exploration of the mundane (everyday, or routine, ‘worldly’ existence) of young women in a city, Delhi in this case. Many documentaries have archived the stories of the survival of the poor in the most adversarial urban contexts: Bombay Hamara Sheher , Jari Mari , etc. Mera Apna Sheher looks at the city from a gendered perspective, representing not just the aspect of exploitation and survival but the desire of the female protagonists to belong to the city, and to make it their ‘own.’ There is a clue to this in the double possessives in the title: mera (my), apna ( own ) . Unlike Patwardhan’s rallying cry of humara (our), the sense of ‘owning’ invoked in Jain’s film is decidedly more personal yet the peculiar genitive claim makes sense only when infused with a strong sense of a gendered collective. There are three parallel tracks in the film which depict the city from three different perspectives: the first is that of the Woman in the City and her use of different city scapes, with which the film begins; the second track portrays three female drivers traveling the urban roads and their accounts about their relationship to the city; the third track is of a stationary camera observing the city from a window in a middle class neighbourhood, depicting the same street at different times as quiet and raucous, uneventful and hostile.

The sense of the personal invoked in the film is diffused, unrooted—yet also grounded in a feminist history and politics. Through its interested observation of the lives of lower class working women, Mera Apna Sheher documents the experience of the Woman in the City whose sense of freedom is located in the fraught intersection of anonymity and misrecognition. This reading is exemplified through one statement made in the film: Suneeta, one of the drivers, comments that she finds it easier to drive elsewhere in the city than in her own basti or locality, where everyone is watching her. Anonymity and belonging paradoxically come together through the negotiation of alienated space.

The women’s movement in India from the 1970s onwards has created opportunities for women to claim the city for various purposes: education, employment, healthcare, etc., on an everyday basis. This has transformed the urban spaces in more than one way. Women as domestic help, municipal workers, security guards, teachers, nurses, receptionists, doctors, housewives etc. are using the urban public spaces for various purposes. As Sameera Jain puts it: “We all know and understand the gendering of spaces or that space is gendered; I felt I wanted my own idea, my own voice…” When she uses her own voice, she turns the relationship between space and gaze on its head. Mera Apna Sheher is an experimental documentary where the story of a great metropolis does not come through its history, its heroes, but through the tenuous gendered relationships that organize the possibilities and limitations of everyday existence in the city.

In The Practice of Everyday Life, de Certeau deploys the categories of “use” and “belonging” to draw our attention to “the notion of belonging as a sentiment, which is built up and grows out of everyday activity.” For instance, regular walks (and other such uses of urban spaces) are a part of everyday existence which also construct a personal sense of attachment. For a woman the negotiation with the urban spaces happens through her gendered identity within relations of patriarchal power. The concept of belonging is usefully explored by Jain through the Woman in the City, her collective character in Mera Apna Sheher. Our first encounter with this character occurs in the opening moments of the film when we see a solitary woman sitting calmly at a bus stop who suddenly starts making some gestures towards the camera, maybe to grab our attention. The scene moves to a corner tea stall bustling with customers, serving of tea, selling of cigarettes and movements of people with faint sounds of cricket commentary in the background. In a passing shot we also get a glimpse of a woman sitting close to the wall behind the tea shop, maybe cleaning cups, or part of some chore related to the shop. After establishing this slice of everyday what comes into focus is a woman who goes past the tea stall a couple of times, stand in the corner and then buys a chai, and later goes and asks for meethi supari (sweet beetle nut) and then again just hangs around there. Her presence makes the audience uncomfortable and jarring for us and for all the characters within the frame. We constantly ask: Who is she and why is she there? The male reactions within the frame are of meaningful smiles and jeers, all of an understanding of who the woman could be or how her presence calls for their reactions. The gendered nature of city space becomes apparent through these encounters.

Later the Woman in the City is there in a park leisurely sitting, also lying down, scratching her thighs, and gazing around. She attracts a lot of attention for being alone, and for being so relaxed with herself. Men look at her, go past her again and again or sit across her laughing at her, imitating her gestures. The total lack of purpose in what she is doing is bewildering for everyone, and so is her unruffled ease, even with the looks. On another occasion, the Woman is standing near an arterial road in no hurry to cross it and as it should happen, a bike with two riders moves in dangerously close to her and them goes ahead. Immediately after that a car stops in front of her and waits for her attention. In absence of a response from her it starts reversing to come closer and pursue its chase as the woman first does not react to it and then getting its intention starts walking away from it. These incidents take us back to De Certeau’s term ‘belonging’ that I had invoked earlier. As the scenes from the film indicate the sentiment created here is of fear, discomfort and alarm. City here changes from a mere geographical setting to a space providing norms for gendered behavior. It begins telling women that their presence in certain spaces will have repercussions. Tovi Fenster’s observation rings true: “belonging and attachment are built here on the base of accumulated knowledge, memory, and intimate corporal experiences of everyday walking. A sense of belonging changes with time as these everyday experiences grow and their effects accumulate.”

The second track is that of two women in a moving car, one driving and the other in the passenger’s seat, talking about their driving job and how this role plays out in the city. In the first shots of this parallel narrative there are two women in a car—one is driving and the other one is the co- passenger. It soon becomes clear that both are professional drivers who have chosen this career after being trained by Azad Foundation. In another shot, there are three women standing in the parking area away from other male drivers aware that they are being observed and being talked about but are undeterred by this fact. The two women going around in the car talk of the joy of driving but also express their anxieties and fears being stared at the crossroads, of men speeding along their car, the difficulties of getting wet and of using toilets. In a curious toilet scene where the women walk for a while to reach a public toilet meant for women, the dark corridor and the bad maintenance are used as indicators of the indifference with which the city treats its women.

The third track is in the observational mode where the camera from the window of a house captures a by-lane—where men casually cross the road and pee against a tree; across the road is a walled play ground where we can see young boys play; there are occasional scuffles on the road between drivers; pedestrian walk; a mélange of various activities are represented in this trail. But this unhappening road of the city changes when the Woman in the City decides to lazily sit on the pavement— relaxed, leisurely, again makes a claim on the city. Through the episodes of women at work-driving around the city, woman in leisure-being in the city, the concepts of use and belonging are being brought together. ‘’Use’’ as everyday corporeal expression of conducting one’s life and fulfilling various chores is represented through the roles of the female drivers – while learning driving in the ground, while taking orders from the bosses or while talking about various experiences of driving. These examples of use come alongside taking a walk around India Gate or having a candid chat with another driver friend while moving across the city in the car. These scenes depict how urban spaces have a bearing on various dimensions of gender relation.

The experimental quality of this film comes from its seemingly unstructured plot, use of a hidden camera along with the ordinary ones, shaky and hazy images and also from the unhurried way with which it shares an experiential moment. The pen camera placed in the bag of the Woman in the City records the reactions of various men- amusement, unease, curiosity—clearly marking this figure as out of ordinary. As the Woman in the City, Komita Dhanda enacts the part of a loitering figure. She is not the female counterpart of Baudelaire’s flaneur, the flaneuse rather a pedestrian who is body negotiating the borders of her limits. So, the public spaces which get privatized by rampant masculinity and acquire symbolic meaning of fear and insecurity are being disrupted by the Woman in the City who refuses to take the responsibility of inviting aggression and violence by turning her gaze to the city and pushing the borders of restrictions and control.

Madhumeeta Sinha teaches at English and Foreign Language University, Hyderabad.

madhumeetasinha@gmail.com