Introduction

Growth in urbanization sees more and more single men and women migrating to the towns and cities for study and work. Though they are integral to the ‘growth story’ of new India very little attention has been paid to their quotidian experience of finding a place to live in the city. Suspicion, scrutiny of their conduct and actions and direct discrimination marks their experience of living as single young people. While both men and women face similar problems, these practices have divergent impact on men and women.

Campaigns such as Why Loiter (see interview with Pinjra Tod and Madhurima Majumdar’s essay in this volume) have consistently highlighted the gendered nature of public spaces in contemporary India. Several urban activist networks have highlighted lack of public toilets and proper street lights. A certain masculine gaze marks women who loiter in the public spaces as ‘sexually available, restricts women’s ability to legitimately claim public space. On a different note, Lukose (2009) showed that young men and women in the public educational spaces present themselves as consumer citizens in the post-liberalization world. However young women from poorer and non-dominant caste background get excluded from the public domain even in this reframed citizenship.

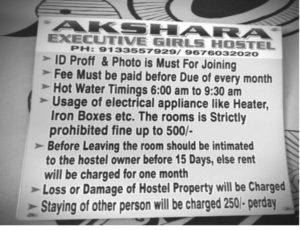

How does gender work in the residential spaces of the city? We have very few accounts of gendered dimension of residential spaces in big cities. Melkote and Tharu’s 1985 study of two working women hostels in Hyderabad had discussed the day to day scrutiny which was the norm that women residents faced. Pinjra Tod campaigns amply demonstrated that such gender differentiated surveillance continues to be the norm in university hostels across the country. The film, ‘Bachelor Girls’ (made by Shikha Makan) documented the tortuous experiences of metropolitan and upper middle class young single women in the City of Mumbai. It showed that the severe restrictions on their mobility and surveillance on the conduct demonstrate the hostility of even the most advanced urban space to the presence of single young women.

What does this hostility indicate? Is there a continuum of surveillance between the public and the residential places? How does it affect single women’s mobility and life? Who bears the costs of such surveillance? And what does it tell us about the gender of the city?

Four Locations, four experiences: Day-to-day negotiations of young migrant women in Hyderabad

The following statements were made to us in the course of interviews to understand experiences of young migrant women to the City of Hyderabad. Hyderabad is a city known for its Nawabi culture; for being the epicentre for separate Telangana movement, in which university students had played a crucial role and for being an IT sector hub which attracts thousands of youngsters every year. Each of these women ‘belonged’ to the city’s advertised faces and was trying to access different kinds of residential spaces such as university hostels, private hostels, PG accommodation and rented flats. Each brings into focus the gendered particularity of these imaginaries of Hyderabad. They make us ask if women were thought to be part of these different imaginaries or sought to be incorporated in this particular manner.

#1. “It was terrible. As I told you earlier mostly they asked questions like what do you do and who is going to stay with you? So there was this junior who was looking for a house because his younger brother was coming to stay with him so we kind of went around together looking for the house and everybody assumed that he was my boyfriend. I was like, look at him? He is 100 years younger than I was. Even if he was, you can not ask such things directly from people, it was like rishta kya hai? (what is the relation?) If you are staying then it is 8000. I said that but the broker said it is 5000 They said but no if YOU people are staying it is 8000. We will keep our eyes closed if you pay us 3000 extra every month.” – Anindita, a PhD scholar.

Anindita, who studies in one of the central universities of Hyderabad, narrated this incident that occurred during house hunting near her university. As a migrant student from West Bengal she initially stayed in the campus. When the administration changed accommodation provisions without a proper discussion with the students, Anindita and several other PhD scholars were asked to leave their single seated rooms or were asked it to share with one or two more students. PhD being a stage of research where researchers need space of their own, Anindita decided to shift out of the campus. During her interview, she also discussed how her lifestyle and vision towards world had changed after she had joined the university. She had become vocal after realising that she needed to express her opinions. Campus life had also taught her that gender segregation is forced by society. Campus spaces broke such strict segregation even though it sometimes enhanced it too. That was the reason why she didn’t think twice before house hunting with one of her male juniors. In this background, when she had to go through the grilling in the process of house hunting, she was outraged to see the scrutiny university students faced. She also shared with us the experiences of her friends, where such scrutinies got multiplied due to caste, religion and race of the students.

Her narrative highlights the type of gaze that university students face in residential spaces. She was assumed to be the partner of her male junior, thereby reducing her chances of getting a house cheaply. It is well known that the presence of these migrant students creates an ‘abnormal’ space in otherwise so-called ‘normal’ atmosphere of the residential areas near these universities. These localities become the beneficiaries of increased commercial activity by catering to the needs of such students in the form of small eateries, second hand bookshops, and used cloth shops. But the local residents maintain their ‘normalizing’ gaze on these these abnormal women, claiming to accommodate them only for economic reasons.

#2. Nothing happened in the hostel but I faced the situation in the city once or twice. When we got late in the night while returning to the hostel.. Like when we went to Charminar and were returning to the hostel. Sometimes it would be 7 or 7.30 PM. I am speaking of a month ago.. A friend and I were returning and heard this comment (from the men standing there). ‘Look at these women from the Urdu University who are out late in the evening. Women now have got too much freedom” – Rafath, a student from a central university in Hyderabad.

Rafath, a student from another central university shared her narrative of being judged by local community around her university. The comment “Urdu university ki ladkiyon ko bahut chutt mil gayi hai” did not judge Rafath and her friend as two individuals. Their act of being ‘late’ was seen as lack of control exercised by their university. This university distinguishes itself from other central universities in the city for having very strict hostel timings for women students. They need to return to the hostel from classes before 6 PM. In the recent past, the women students agitated for flexible hostel timings to avail library and other academic facilities. A few students, including women, were punished by the administration for raising these concerns.

Given this background, one needs to understand the anxieties among the local residents to ensure that ‘these girls’ are kept in control by the university administration. Borrowing from Hubbard (2012), one can argue that these women students are seen as unattached sexualised bodies by the local residents. The presence of such unattached women creates a threat to the balanced ‘order’ of the society where each woman is placed in a familial or community setup. Women who access the city space independently can give rise to such aspirations among the local women who are bound by the home rules. It is such a logic that seems to guide the controlling gaze of local residents.

#3. People from this place had called. They actually called my friend and my friend called bhaiya (elder brother). So I spoke to bhaiya and told him the exact circumstances. I told him that it was also raining and there was a small shed for pressing clothes. So I told Kiran, my friend who was with me, that since it was raining, wait for a while then go. So he waited and didn’t even sit down because he thought people might think he was (or we were) doing something wrong. He left after the rain stopped. By that time bhaiya got to of know this and he called. He said that some third person told him about me standing with a boy in that shed, and so he was hurt; and that I had told him then it would have been better. I said yes, I accept my fault that it was raining and I told him to wait for a while then go. So bhaiya said okay. Neither I nor my bhaiya liked it that a third person had told him”. Radha a resident of a low budget private hostel in Hyderabad.

Radha belonged to a business family and had the option of joining the business after completing her engineering degree. But she chose to come to Hyderabad in search of an independent identity. As the conversation indicates, this incident occurred when she asked one of her male colleagues to drop her and had to wait under some shelter with him as it was raining. By the time rain had stopped and her male colleague had left, her brother got to know about it as one of Radha’s hostel mates had called him informing about the ‘situation’. Radha’s brother then gave her a ‘brotherly’ call to alert her of her duty to inform him of her whereabouts.

It’s this self-surveillance that made Radha regret asking her male friend to wait and not informing her brother about it. As a woman who chose to come to the city over staying back with the family business, the idea of gossip about herself was so traumatic that she blamed herself. Even though she didn’t like the fact that, that her hostel mate informed her brother, she chose not to confront her.

Radha, like many other women saw her move to a bigger city in search of their identity as a ‘gift’ from their parents. This keeps them in a deep sense of gratitude and indebtedness that they don’t want to do anything ‘wrong’ that might hurt their parents. This self-surveillance is supplemented by the control and gaze inside private hostel spaces where she stayed. Hostel wardens and in this case hostel residents also act as the voice of women’s parents. Small acts like talking to a male colleague are seen as a ‘breach of trust’ towards the parents. More than administrative control, as found in university hostels, its the moral control that seems to endorse the inner guilt felt by Radha.

#4. ”I remember once…. I think he (the house owner) used to stay in Mehdipatnam. When he used to come to this side of the city, to the house next door or next building which belonged to his cousin, and they used to drink together. There was a small room down the stairs from our flat where they used to drink. So there were quite a few times when me or my roommate were going down, that the owner came and asked “chalo madam join kar lo humlog ko” (come join us for drinks). He told me once “aa jao madam, pi lo hamare sath, aap log to pite hi ho”. (since you drink come and join us for drinks). He used to look us in a certain way because we drink and smoke.” – Sangeeta, a corporate worker in Hitech city of Hyderabad.

Sangeeta had come to Hyderabad to study MBA and later joined a multinational company in Hyderabad. While talking about her experience of the city, she described how she constantly felt as an ‘outsider’, whether it’s her office or at the residential places where she stayed. She insisted that there is a widely prevalent notion in the city that such ‘outside’ women are of a certain moral type and can therefore be treated ‘differently’. She said that the office did not think it important to arrange safe transportation for her as it was assumed that she can manage ‘on her own’. It is precisely the same reason her landlord wanted to join him for drinks and smoke as she was seen as a woman who is free and has nobody to control them.

Sangeeta’s narrative forces us to see the issues that single women in the city face for ‘being on their own’. Many women in our study shared their feeling that staying away from home brings a sense of independence and freedom, where they can lead their life according to their own will and follow their aspirations. They want to be seen as independent women who can look after themselves. However, the same single status also brought in the sexualized gaze where their independence is seen as being sexually available.

The new moral guardians: The anxiety to control

When Hubbard (2012) argues that unregulated sexualities in any city create an imagined danger, such dangers are mapped onto the bodies of the migrant single women who have come to the city with their own dreams and aspirations. Such dreams and aspirations to study and work that fit the growth narrative of these cities are welcomed, but when these get reflected in a changed lifestyle, relationship choices and new mode of conduct, different social structures in the cities take over the role of ‘guardians’ to establish the ‘order’ of the city. It appears as if the larger society takes over from the family to control these women.

We can see that landlords, hostel owners, hostel-mates play this role at an everyday level and universities and other such institutions also taking over as the custodians of single migrant women. It became even more clear during the random hostel checking in universities like HCU and JNU that not only is the sexuality of young people vilified but that the university retains the right to be the guardian of the students in the absence of their family members. In a recent incident, video footage was taken as ‘proof of unseemly’ conduct of the young woman to her family members. In another well known incident at MANNU, one of the female students who had raised the issue of hostel and library timings was called an ‘agent’ of the Pinjra Tod movement implying a paid trouble maker. Bizarre arguments are used to trivialise the concerns of young women students.

Such attitudes of private hostels and university administration also cannot be seen in isolation. In recent years public vigilantism against publicly visible modern women and youth has increased manifold, be it the public humiliation of a pub-going woman in Guwahati or the previous attack on pub-going women by the Sri Ram Sene or Telugu TV channels following women inside bars/pubs or Operation Romeo in UP or the outrage in Kerala against kissing in public. Such daily acts of vigilantism against modern youth, especially against single and independent women have become ‘normalized’. Its only in this wider context that the experiences of single migrant women such as Anindita, Radha, Rafath and Sangeeta who face crude, subtle or shrewd scrutiny can be placed. It is the determination and struggle of these women, which seems to be negotiating a wider space for themselves and others in cities like Hyderabad, even though neither the cities nor its structures seem to be ready to welcome the single women like them.

References:

Lukose Ritty A. 2002. Gender Youth and Consumer Citizenship in Globalizing India Liberalization’s children Duke University Press, Durham and London.

Melkote Rama and Tharu Susie J, “An Investigative Analysis of Working Women’s Hostels in India”, Signs, Autumn 1983, pp. 164-171.

Hubbard, Phil. 2012. Cities and Sexualities. Routledge, Oxon.

Phadke Shilpa, Khan Sameera and Ranade Shilpa. 2011. Why Loiter: Women & risk on Mumbai Streets, Viking, Penguin.

Rani Rohini Raman works at Anveshi Research Centre for Women’s Studies, Hyderabad.

rohini.redstar@gmail.com